MAIDEN, MOTHER, CRONE

spring-summer 2003

tuscany

As a teen and into my 20’s, I let my youthful exuberance carry me into explorations of my idealistic notions of love, of other people, and of the world. I prided myself in the fact that since I was 17, I had left my home country every year to travel Europe, Africa, and South and Central America, until I left the US altogether at the age of 25. It was a big wide world to me. My Venusian principles gave infinite pardons to less-sincere friends and lovers, while compelling me to taste the many pleasures of love.

When I met Diana, I saw reflections of my earlier self. An American woman living in Italy, she was the picture of carefree discovery of Life. A bouncy blonde Californian, she morphed into a stylish European with all of the class of Grace Kelly becoming a princess. Though her tastes were simple – maybe only wearing a blouse and three-quarter-length pants – she threw the accents on with a splash: zircon-studded sunglasses, a lime-green silk scarf, or opera pink pumps. Her English by now carried Italian inflections and she moved her arms in grand sweeps to make a point. As Coco Chanel put it: “Elegance does not consist of putting on a new dress.” Since Diana lived on another mountaintop in our valley, we would rendezvous down in Bagni di Lucca. Her phone call would often come just when I needed a break from my routine:

“How about a cappuccino? I’m craving an almond-chocolate biscotti. I can be at Café Roma in half an hour!”

Like her goddess namesake, Diana (Artemis to the Greeks) was the Maiden: independent, impulsive, fresh, spirited, and seductive. Diana had fallen in love with a gentle Italian man named Sileno. Irrespective of their physical contrasts — her straight blonde hair, his black curly hair; she short, he tall; her fair skin and blue eyes, his dark skin and brown eyes – they shared a relaxed understanding between them.

When she discovered she was pregnant, she came to me for counsel. It was only natural, since I am a mother, but in addition, her deeper questions required a wise woman, which I realized I was becoming. Diana and Sileno decided to marry, and I stood up for her at the altar. Since she asked me to accompany her in the birth, we began coaching sessions, which went well beyond the breathing and pelvic muscle exercises. If I had not chosen to work as an environmentalist, I would probably have become a birth activist, so strong are my feelings about how we bring children into the world. Diana recognized my knowledge and dug it out of me, devouring every experience, idea, and book I had to offer.

When male doctors took the birth process away from midwives, serious harm was inflicted upon the human race. Our very notions of human nature, as well as our identities of self, originate with our birth. The dominator mentality completely devalued the woman, even to the point of proclaiming she was soulless! In the 13th century, Thomas Aquinas explained conception like this: a soul, contained only in the male seed, plants itself in the “soil” of the female womb, the woman only being the flower pot for the new life to grow in. Modern thinkers may jeer at such a notion, yet our ideas of conception describe a “strong, active” sperm “forcefully penetrating” and delivering genes to the “large, passive” egg that is “adrift” in the womb, which conform nicely to the stereotypes of the aggressive male and passive female. What science now reveals to us, however, is that the surface of the egg is sticky, which attracts the sperm to build a bridge of protein molecules to it, so that the two stick together. [Sacred Pleasure, p.289] Instead of “naturally” dominant sperms and passive eggs, it turns out that conception is actually a cooperative process — a bridge-building collaboration between the two.

The pregnant woman, to my eyes beautiful as her body blossoms with growing life, is considered by some to be fat or unsightly. In the 1940’s, doctors were advising women not to gain any weight when pregnant, presumably so they would still be sexually appealing to their husbands. While women’s breasts may be sexually arousing, lactating breasts are regarded as gross or offensive, as any woman who has breast-fed in public can tell you. Diana would not be bothered by such judgment, however, as she already proudly sported her rotund belly with midriff tops.

Neither she nor Sileno wanted a hospital birth, but I do not portray myself as midwife, so I told them to find someone responsible to catch the baby. They found a birthing center near Siena that offered midwives, tubs for water birth, large private rooms, and adjacent proximity to a hospital . . . the best of both worlds. When I had given birth to my son in Puerto Rico, I had made the difficult choice of a home birth, as the hospital, an hour away on a curvy road, had been unresponsive to my requests of low lighting, the freedom to walk, my birth assistants present, and keeping my baby with me. I had to take responsibility for the birth, which is how I got so educated about the process, because I knew emergency medical care was a difficult hour away. I assembled my team: a midwife, a breathing coach, an affirmation coach, the father of my child, and another helper. Even though the room contained flowers, candles, and soft music, I had sterilized it and everything in it. I spent my 12-hour labor first floating in the ocean, then sitting under the abuelos mangó trees, then pacing in the house, and hanging from a low bar, assisted by my team. I felt like I was on an LSD trip: the sea had never glowed with such intense turquoise luminosity, the trees bent down and held me, and when I was uttering deep, primal cries to push my baby out, the cows bellowed across the fields and our dog howled into the night. All of Creation seemed in concert with my labor. When my son was born, he gave out a little wail, and then, laying on my chest, his umbilical cord still pulsing vital nutrients into him, he looked around at all of us. Our first gaze communicated a profound love, an eternal bond. I had become a mother; it was my first inkling of archetypal power beyond my comprehension.

Doctors say that babies are born nearly blind and are oblivious to the world. Circumcision does not really hurt them because of this obliviousness. In a strict medical situation, women are left to labor alone, strapped to their bed with a fetal monitor inserted into their vagina (to give a printed record of the labor in case of future lawsuits). If the labor goes “too slowly”, or the woman runs out of stamina, contraction-inducing drugs are administered. If it all goes on “too long”, the baby is extracted via Caesarian-section surgery. A spank on the bottom to get the baby to cry (voilà! a fitting reception to a violent world!), the cutting of the cord (which deprives the child of foundational immunity), and then the baby is whisked away to be “cleaned up” (of the waxy vernix which protects the newborn skin), weighed and measured. If they are lucky, mother will get to hold her child, but soon enough the baby is placed in a crib, often in a nursery with other howling newborns. After nine months floating in a warm, dark womb, the newborn must contend with a chilly, white room flooded with fluorescent light. With such a brutal, frightening entry into the world, the baby can turn only to his/her blanket for comfort. How to recover from such a shock?

The modern birthing situation institutionalizes trauma, so that emotional self-suppression and the donning of psychological and muscular “armor” become survival tactics. Welcome to the cold, cruel world!

This was the kind of birth I had refused for my son, and Diana was now refusing for hers. During my pregnancy, when I had to become a relative authority on birth in our rather isolated island home, I learned how crucial our entry into life is. I read Ideal Birth by Sondra Ray. As a rebirther, she had heard client after client recount under trance their traumatic childhoods, all the way back to their births and even the womb. So her logical conclusion was to stop traumatizing people right off the bat.

The most important lessons of our lives we learn in the first minute after birth. We are forever imprinted with the conditions of that moment. Astrology is based on this fact. The next most important lessons happen in the second minute. And so on until about age six, when our personalities are 90% formed.

Under the patriarchal medical system, what lessons do we instill in our children?

- When the going gets tough, get numb. (This is from an anesthesia-induced feebleness during the labor. Sondra Ray proposes that the drug culture of the 1960’s was a direct result of drugged births in the 1950’s.)

- It is a painful, violent world.

- You are alone, and that is scary. (Imagine the terrifying isolation of lying alone in a completely alien room with a dozen unseen, screaming inmates around you.)

- If you cannot be with the one you love (Mother), love whatever you’re with. (Babies will bond with the blanket in the crib, which is why kids will carry around their “security blanket” for years, until it is but a scrap of cloth.)

- You are separate from the Earth (Mother).

Since Diana had taken the full download of my perspective on birth, and we had worked together for months, she, Sileno, and I formed ourselves as a team to bring in their child. “Anything can happen in birth, so mentally get ready for anything. Prepare for labor like your training for a marathon,” I told them, and they did. Finally, in the middle of a summer’s night, the three of us found ourselves in their car, speeding toward Siena. Sileno was concentrating like crazy on driving, and I was timing contractions and breathing each one with her.

Once in the comfortable room, we got into our rhythm: breathing, talking, resting between contractions. The midwives peeked in on us, nurses brought us herbal tea. Hours passed, and Diana felt like getting into the birthing tub. As she changed positions in the warm water, I chanted affirmations to her:

“They are not contractions, they are expansions.”

“Each expansion brings you closer to seeing your baby.”

“Oh, oh, opening. Opening and opening.”

“You are passing from the archetype of the Maiden to the archetype of the Mother. This is your initiation. You can do it. You must do it.”

“From time immemorial, women have birthed their babies. Reach into this river of eternal knowledge. Your body knows how to bring this child into the world. Let your body do what it knows how to do.”

Hours more passed. Her lower back hurt, and Sileno massaged her. She felt faint. She threw up. Labor is work, no doubt about it. The patriarchy defines bravery as risking one’s life to defend one’s own, or to kill the dragon. But all mothers know what bravery it takes to risk one’s life to bring in a baby. Birthing requires a concentrated effort of endurance, strength, power, hope, and devotion. And once it starts, there is no turning back.

Finally, when the birth had seemed imminent for an excruciatingly long time, the midwives and we conferred. “Maybe she needs to get out of the warm water,” one midwife suggested.

“Yes, that’s right,” I concurred. “She’s an Earth sign. She probably needs her feet on the ground.”

Once out of the tub, Diana squatted on the ground, supported by Sileno behind her. With both hands on her knees, I coached her through the last pushes. Another roaring push, and the baby squirted out into the midwife’s waiting hands. There was no cry, and the baby was blue. Diana could not see the infant, but Sileno did. He blanched white. “My baby! My baby!” she cried.

I met her eyes with mine, emanating my strength at full power. “Hang on, Diana,” I said firmly. The midwives’ hands were busy, and one of them reached for a phone.

Still no cry. Within 30 seconds, a team of doctors and nurses swept into the room. The midwife cut the cord. “No!” Diana screamed. “Don’t cut the cord! No!”

They whisked the blue baby to a nearby table, where they cleared his lungs of meconium. He had inhaled his first bowel movement during the labor process, and was choking.

“My baby! Where’s my baby?” Diana was hysterical.

“Look at me!” I commanded her, pointing two fingers at my eyes. “Your baby is not breathing yet, but you have to keep breathing. Breathe with me now, Diana.” Together we did slow, deep breaths.

Quiet commotion at the table, and then – the cry. They immediately brought their son over to Diana and Sileno, and we all bawled. The room resounded with our cries of relief and joy. Sileno told me later that at the instant of the birth, fatherhood hit him like a freight train – immense love, cutting worry, and heavy responsibility. Would his child live or die? What could he do?

Soon we had Diana settled into the bed. She and Sileno cuddled their offspring in the quiet afterglow. I cooed encouragement to the newly arrived one: “Welcome to a beautiful world.” “From spirit you come, in spirit you will live.” “We all love you.” “We’re so glad you’re here.”

Then I saw it . . . Diana’s face had changed. The soft, fresh, round face of the Maiden was no more. Before me was the Mother: powerful, triumphant, sharp, fierce, loving. I have seen it many times, yet it never ceases to astound me, how in the space of a few hours a woman can visibly transform so completely. Once again, I had been honored to witness the Maiden’s metamorphosis, and to welcome a new soul into the world.

Diana had done it. She had put on the mantle of the most powerful archetype on Planet Earth. She had passed through the initiation of the Mother.

((( )))

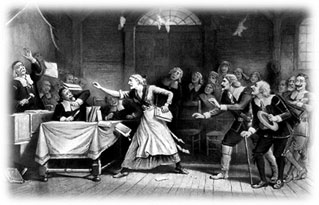

Here, the Triple Goddess as 3 fearsome witches. Warhafftige Zeitung von den gottlosen Hexen … zu … Schletstatt by Flugschrift Reinhard Lutz (1571)

I loved the occasions I could work as a doula, or birth assistant, because of how immeasurably gratifying it was. Were I living here during the Middle Ages, however, I would have had to risk my life to carry out the job, for midwifery and related practices amounted to witchcraft. Witches were tortured and burned at the stake for – among their many transgressions – counseling others, concocting herbal remedies, healing the sick, and helping women in childbirth . . . especially helping women in childbirth. Officials of the “Holy” Inquisition stated, “No one does more harm to the Catholic faith than midwives.” (Malleus Maleficarum, p. 66). Inquisitors ostensibly were preventing “witch midwives” from devouring children and offering them to devils, but their deeper reasoning was that since God had inflicted the pain of childbirth onto women for Eve’s crime, to do anything to lessen that pain was in direct defiance of the will of God. [The Crone, p.128]

The most experienced midwives and healers were, logically, the elder women of a village. When the Inquisition burned to death the old women, it was as if a library of age-old knowledge went up in flames with them, for these wise women knew more than which herbs to use: they had the know-how of birthing and rearing children, and by extension, of maintaining the social framework in which humanity could thrive. Prehistoric art is predominantly by and of women – and especially pregnant women. The Venus of Lausell (25,000 BCE), birthing figures from çatal Hüyük (6000-7000 BCE), et al, celebrate the promise of new life through the body of a woman. Historic art, by contrast, is predominantly of men wielding weapons upon their human brothers, celebrating the power of destroying life.

After 500 years of genocide by the Inquisition, the remaining women either took their knowledge deep underground, or they learned to be submissive, uninquisitive, and passive. The Crone, the Wise Old Woman, was, at the least, stripped of her power, and nearly obliterated from cultural consciousness. As I made my way on my menopausal journey, I set my sights on becoming a crone. But where were the guides for my crossing? In the throw-away society I came from, old ladies were all but discarded, relegated to bridge games or quiet widowhood or nursing homes, once they were past the point of help by cosmetics, face lifts, and hair dyes. Society’s scheme, governed by the imposing Venus archetype for women, was that when you could no longer look younger, you could not be sexy . . . and there went a woman’s worth! Of course, I intended to be a sexy older lady who was proud to reveal her age, or as Jean Shinoda Bolen puts it: a “juicy crone”. My capacity for love seemed to be growing — not shrinking — and even though the expression of my sexual urges was getting overhauled, I did not feel it was being snuffed out.

My good fortune would place me, a baby crone, way up in this Tuscan mountaintop village, where the very cobblestones seemed to guide my feet along a time-tested path for growing older. My two best friends in our village were Renata and Suntina. Renata was 76, and Suntina was 83. Both lived across the small piazza from us in houses that had been in their families for generations.

Renata was stalwart as a horse. Her thinning brown hair revealed patches of scalp, but her bushy eyebrows made up for that. Her perpetually ruddy cheeks accentuated the curl of her lip when she listened, as she was always ready for an argument, and her piercing brown eyes were a natural bullshit detector. Had Renata lived during the Middle Ages, she would have been one of the ones they made walk into court backwards. (Inquisitors feared the “evil eye” of a crone, for certainly women in their power would have cursed their immoral

The Witch, No.3, by Joseph E. Baker (lithograph by Geo.H. Walker & Co., 1892)

high-jinks, so the men who sat as judges were unable to look them in the eye.) Even though Bagni di Lucca had a mayor, a pleasant man who lived in our village and was happy to display the official ribbon across his chest, Benabbio had its own unofficial “presidenta”, Renata. A dispute among neighbors? . . . a parking problem? . . . clarification of a rumor? Go see la Presidenta, though odds were she was already aware of the situation and had a common sense solution for it. Renata wore an apron (yellow with black dots) always.

Suntina reminded me of Mighty Mouse: 4’10” short, petite, and surely able to fly through the air, with or without a broom. She kept her silvery hair cropped short so it required no fuss. In spite of their delicate form, her hands could do anything, from shucking peas to fixing the toilet. She tended her olive trees and grape vines daily, and from my window I could watch her climb the mountainside road with a heavy sack of fertilizer perched atop her head. One afternoon, Alex and I were hiking along the terraced groves and we heard her whoop. Looking around, we could not see any trace of her. Then looking up, we spied her in the branches of an olive tree. “Suntina, what on Earth are you doing up that tree?” I asked in my halting Italian.

She gave a sideways look as if to say, “Why is this americana always asking obvious questions?” and answered, “Haven’t you noticed it’s the olive harvest?” and then laughed good-humoredly.

She told me stories of how the Nazis had taken over their house during the war, and her family had fled into the forest, where they and other villagers survived on chestnuts and wild greens.

Renata and Suntina took a passegiata, a hike into the forest, every day. I would hear the clack-clack of their walking sticks on the cobblestones 15 seconds before Renata’s voiced boomed into our kitchen window in long syllables, “Hrei-be-ca! Hrei-be-ca! Andiamo!” (“Becca, let’s go!”) As often as I could, I joined them.

One fall afternoon we climbed the mountain road above the village. I noted what a strange trio we were. I wore my vibram-soled, gore-tex lined, double lace-up hiking boots; they both wore rubber garden boots. I sported my black aluminum telescoping alpine walking stick; they kept a slow but steady beat with their smoothly worn wooden sticks, yarn-wrapped at the top. A jute-woven bag was slung over Suntina’s shoulder; I had a nylon backpack and carried a straw gathering basket. The chestnut woods glowed golden with autumn’s light, and we enjoyed the sun’s warmth, as the season’s damp chill had already begun to creep along the forest floor. Our mission was mushrooms. As they clumped up the narrowing road in their galoshes, we met people coming down with empty bags, “What a bad mushroom season,” the people descending commented. “Look what I found!” exclaimed one middle-aged lady, showing us two porcini mushrooms.

“Wow,” I said as we entered the forest, “Do you think we’ll find any mushrooms?” They both snorted simultaneously and cackled.

Barely breaking the pace of our walk, they would bend down, lift up ferns, look behind logs. I did, too, but there were no mushrooms to be found. Then, going to the same place I had just looked, they would pluck a mushroom, then another, then five. Frulla, like spotted, tan parasols, were sometimes as broad as my face; golden brown boleto dei pini; and meaty porcini, whose name means “little piglets”, squealed in anticipation of landing in my skillet (or it seemed to me). Before long, my gathering basket was full, and we could fit no more into our bags, either. These crones knew the forest as well as they knew their own children. Along the way they would point out the characteristics of all manner of herbs, weeds, wild fennel, deer tracks, boar wallows, and snake lairs. Under their tutelage, I learned how to prepare – and savor – wild mushrooms, squash blossoms, wild greens, chestnuts, and an endless cornucopia of garden produce: tomatoes, zucchinis, lettuces, chard, artichokes, fava beans, peppers, radishes, beets, potatoes, carrots, cucumbers, onions, and of course, garlic. Alex was the willing gourmand who sampled my latest dinner experiment. So many of our memories of Italia would be flavors.

In the winter during grey, wet days, I would visit my crone friends in their kitchens. Only once did I see any other room: Renata showed me her dining room, with the long table lined with family pictures, which she explained one-by-one: “This was my husband.” “These were my kids when they were little.” “This was my husband’s car.” While I had vowed that my household would not end up like theirs – the TV, washing machine, easy chair, and dining table all jammed in with the kitchen appliances – by our second winter of heating bills and interior temperatures like a dungeon, our kitchen, too, had laundry and herb bundles hanging from the ceiling, and furniture and appliances gathered around the fireplace. Sipping coffee by the hearth, the signoras would knit while we chatted. When we talked of their deceased husbands, it was as if it was from another life. Taking care of a man, raising children – that was all well and good, but that was over. Now, on the other hand, they could ignore the many rooms of their houses, simplify their possessions, and do whatever they damn well pleased. Their routines – the daily passegiata in the forest, tending their gardens and groves, keeping the gravesites of family and friends furbished with flowers, attending mass, preparing food – were enjoyable tasks. Though I know they both suffered aches and pains, I rarely heard a whimper from them. They awoke each morning eager to begin a new day. I was part of their new days, I know, with my strange questions, creative Italian, outrageous ideas, and silly jokes. When I told them I was just a baby crone and respected them as my elders, they laughed . . . and they hugged me, too.

The stages of life are known. I had been Child who grew into Maiden. Giving birth to a child had initiated me as Mother. Many women gave birth to businesses or causes. Now I was embarking upon my life as Crone. Rounding that bend, I could see what lay down the pike: Death. The Crone is “She who walks with Death”. How many friends and family had Suntina and Renata buried already? Indeed the former inhabitant of our house had been their best friend. One day I was complaining about my menopausal insomnia. “I couldn’t sleep last night either,” said Renata, “so I started counting . . .”

“Sheep?” interjected Suntina.

“No — widows! I counted all the widows in the village!”

Suntina and Renata kept the gravesites clean and said prayers at mass . . . gravesites that held metal coffins to keep people separate from the natural world, even in death, and prayers that hoped for a heavenly salvation from eternal punishment. While my friends’ instincts were right on, the tradition they were carrying – that of funerary priestess – had been truncated long ago.

In pagan times, dying was the domain of the Wise Woman, the Death Priestess, the Queen of Shades, the Goddess of the Underworld. Just as she brought babies into the world as Mother, she could guide them out of the world as Crone. Soothing the sick at their bedside, encouraging them to let go into their deaths, comforting the families left behind, and sending the soul onward in sacred ritual – these were the duties of the old women of a community.

Their archetypal counterparts were the Crone goddesses. Celtic Morgan, one of the Morrigan, was the goddess who levied the curse of death at the proper time. . . and every living being had its proper time. Hindu black Kali’s most gruesome aspect was that of the old hag who decapitated mortals, tore them limb from limb, and pushed them into the transformative process. Tantric Buddhism had dakinis, or “skywalkers”, who could fly in at the moment of death and take in the person’s dying breath with a “kiss of peace”, purportedly a blissful experience. Norse Valkyries gathered the souls of the dead and transported them to Valhalla, the cave realm of the goddess Hel. In Greek mythology, it was a male god, Hermes, who acted as psychopomp and transported souls into the underworld, where Persephone would receive them. The underworld was the place of underlying forces, where the soul re-organized and prepared for its reincarnation. It was not a place of punishment or damnation, which Hel’s realm became under the Patriarchy: a living hell.

Why did she become such a terrifying image? Wouldn’t we all like some grandmotherly comfort in our dying moments? She was demonized because she was a she, and a powerful one at that. The dominator mentality could not allow authoritative old women who held property, managed birthing and dying, meted out justice, interceded with the gods and goddesses, and set kings onto the throne, for pity sakes! Or maybe because she represented Mother Death, who assured an inevitable disintegration of the ego; eliminating her might grant a reprieve from the dreaded blackness of nonexistence. Whatever the psychological basis may be, when they got rid of the witchy old Wise Woman, they arrogantly tore asunder an archetype necessary for navigating one’s passage through life. It seems preposterous that an archetype could be simply ignored by the dominant cultures of the human species. What would happen to those cultures?

Well . . . death would be feared, the very topic studiously avoided. Symbols of death, such as the Crone, would be suppressed. The very process of approaching Cronedom – aging – would be repudiated. Of course, anything repressed within our psyches only lurches out in other forms. Could it be that our collective fear of death has been projected outward in the form of war, murder, and sadistic visions of Hell? Is this the price our society pays for killing off the Crone?

As I wrestled with my menopause and contemplated my old lady friends, I began to see how imperative it was that I embrace my own aging — for my personal benefit, as well as for my society’s. The Wise Woman was no small role I was being called to step into. On my journey I would have to trust my intuitive feelings, listen to Grandmother Growth, and learn what I could from my elders. I gratefully took clues from Suntina and Renata and their easy laughs.

One day I went to Suntina’s house to visit and found her – where else? – in the kitchen. Leaning into her fireplace, she stirred a big black pot that hung on a metal crane and hook above the fire. With her long navy blue skirt and black sweater and short silvery hair, she was Wise Woman personified. After a brief conversation, I ran across the piazza to get my son so he could behold the scene. When we returned, she let us taste her zuppa di fagioli, a thick stew of cannelloni beans, farro (spelt grain), potatoes, cabbage, and garlic, warning us, “But it’s not quite ready yet.” I nodded understanding; the flavors of the oregano, parsley, black pepper, and parmesano cheese would come through with more time . . . and more stirring.

As we walked back to our stone house, my son asked, “So Mom, what was the big deal? Why did you want me to see Suntina cooking?”

“Alex, when have you ever seen that kind of scene before?” I asked him. He knitted his brows and shook his head, so I clued him in. “Halloween! Wasn’t that just like a witch and her cauldron?? OK, there were no bats or eyes of newt, no black pointed hat and Suntina’s skin is not green, but that is where that image came from – from the hearth, from the family kitchen, from women who knew how to cook and make medicines and candles and dyes . . .”

“OK, so what’s your point?” he asked.

“My point is, dear son, that witches are not bad. They are just women doing what they know how to do.”

Alex smiled and told me, “Mom, you’re funny. I know that!” I watched him run up to our house, and in a moment whiz past me on his scooter.

My son knew that, but most of his male counterparts did not. Calling a woman a witch was an insult. Her cauldron, that most feminine of symbols, had been lost in time out of mind. It had been turned into the Cup of Christ that held his sacrificial blood, the Holy Grail, which, significantly, was never found by the valiant knights of the Round Table.

The Dark Mother presided over her cosmic hearth. She received the souls of the dead and cast them into her cauldron where they melted down to their baser elements. Her recipe called for only essence ingredients: energy, matter, thought forms, life force. She stirred her pot round and round, in the continual cycles of birth-life-death-transformation-rebirth. Round and round: creation – sustenance – destruction. There was not just one seven-day Creation; there was perpetual creation. The karmic wheel turned. The masculine and feminine forces of the Universe mingled and created life again and again and again. She was the Great Recycler. She had lived long enough to have gained the wisdom, to understand the phases of life, to know how to stir the pot.

The cauldron – the cave – the pit – the womb – herein resides the power of the Feminine. The Mother birthed from her womb, and the Crone received the dead into her cauldron, where she could make souls ready for the Maiden to invoke. Our ancestors understood this. As I grasped the breadth of such a seasoned understanding, I also felt within me my Maiden’s idealism and independence, my Mother’s sensual delight and tender care, and my Crone’s farsighted sense of justice. I contemplated the awesome responsibility of passing this knowledge on to my descendents. But wait – would there be descendents in a world where leaders were implementing plans of mass destruction, believing it was OK because they would end up in Heaven?

Troubled by this thought, I went to sit by the fountain in the piazza just below our house. The pure, cold water flowed, as I imagined it always had. In a rounded niche in the rock wall by the fountain hung a small ceramic plaque of the Virgin Mary holding her child. Halos around both their heads, the terracotta figures emerged in bass relief. The Christ child raised his hand in a blessing. They looked not Renaissance nor Gothic, but more Roman, or maybe even Etruscan. They looked like they could be from this village.

Thousands of years ago, people probably came to this spot to drink, to fill their earthenware jugs, to chat, to bathe. Maybe there had been a shrine here to the Mother Goddess, who poured out life-giving water at this spring from her body, the Earth. The priestesses would have served her and their community. And all would have honored the elder men and women – the ones who had achieved old age – and with that, the abilities to heal, to prophesy, to teach, to advise, and to protect the people with their guiding wisdom. As the manifestation of the Goddess on Earth, and with the closest gander at the mysteries of death, the Mother’s Mother – the Grandmother, the Wise Woman, the Witch – was the ultimate authority for her children of the human family.

What would it take for the Crone to be restored to her rightful place in our society? I swirled my hands in the water. It would take Renata and Suntina and me and all aging women to step into that place of power and wisdom again.